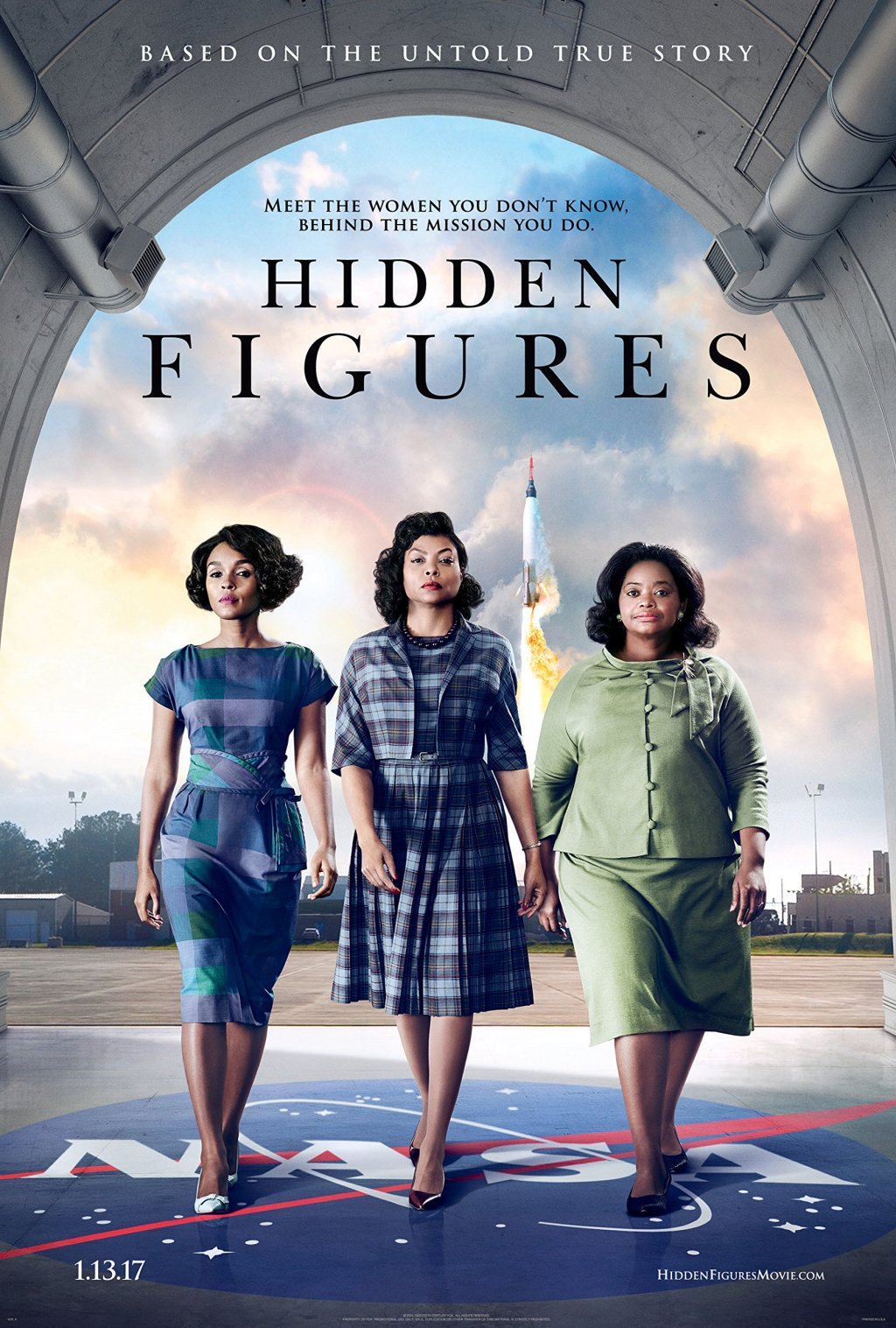

As we celebrate International Women’s Day, I rewatched one of my favourite films that carefully link physics, mathematics, and the sometimes disregarded achievements of women in science. “Hidden Figures” (2016) narrates the remarkable mathematicians Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson whose computations were crucial for America’s Space Race success.

I’ll admit I was initially drawn to the film partly because of Octavia Spencer, whose performance in “The Help” had completely captivated me (and rightfully earned her that Golden Globe!). Her portrayal of Dorothy Vaughan brings such humanity and quiet determination to a woman who saw the future of computing before most of her colleagues did.

These women’s experiences especially speak to me as a woman in cinema studies who surely knows little about advanced physics. In a much lesser sense, my own path of using films as a teaching tool to make difficult topics more accessible mirrors, in a much smaller sense what these women accomplished – finding means to make the seeming unfathomable understandable from many angles.

There’s something powerfully connective about watching these brilliant mathematicians navigate both scientific challenges and societal barriers. While I work to bridge film and education, they bridged mathematical theory and space exploration while overcoming discrimination based on both their gender and background. On International Women’s Day, I’m elicited in creating pathways to understanding – whether through equations or through film – often requires breaking through established boundaries.

For our Physics in Frames study, “Hidden Figures” is very important because it shows intricate scientific ideas through human calculation. Unlike science fiction, which occasionally grounds speculative notions on physics, this film reassembles actual mathematical problems that must be addressed if humans are to reach space. Programming logic, differential equations, and orbital mechanics are barriers overcome by determination and ingenuity; they are not abstract concepts.

The film also offers something rarely seen in physics-focused cinema: it shows how systemic barriers in education and professional settings prevented many talented minds from contributing to scientific advancement. Without explicitly labelling or categorising these women, the film shows how they navigated additional hurdles beyond the already difficult mathematics – from separate facilities to educational restrictions based on their gender and background.

On this International Women’s Day, let’s explore how “Hidden Figures” visualises orbital mechanics, atmospheric reentry calculations, and the dawn of computer programming through the work of women who were, for too long, erased from our understanding of scientific history.

Equations in Chalk and Courage: Visualising Orbital Mechanics

The way “Hidden Figures” turns potentially boring mathematical ideas into moments of human triumph and suspense is among its most potent features. The movie presents a big challenge: how can one visually appealing physics computation?

The response is found in several masterfully written sequences that highlight the physical act of computation and the personal stakes underlying every number, therefore transcending the equations themselves.

Visual power in the scene where Katherine Johnson (Tara P. Henson) works on John Glenn’s orbital trajectory is remarkable. The movie depicts her deriving the new maths required for the mission on a chalkboard filled in intricate equations, the camera focussing on the chalk moving across the board. The way the movie breaks between these scenes makes this one more powerful.

- Close-ups of equations written and deleted.

- The physical strain of the labour as Katherine extends to span large blackboards

- Sceptic colleagues’ reaction shots progressively moving to recognition.

- Riding on every computation, the human implications

The movie does not simplify the physics; on screen, we observe real Euler’s method computations and coordinate transformations. But the film makes us feel the weight of the effort rather than trying to make viewers grasp every variable and constant. The physics is shown not just in the calculations but also in Katherine’s tenacity as she wanders among buildings, blackboards, and briefing rooms.

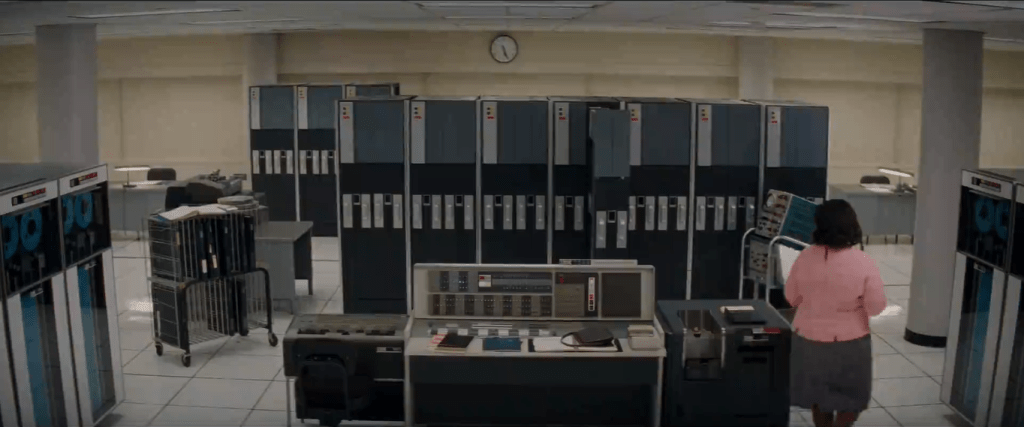

Most of what stayed with me was how the movie presents the IBM computer as nearly a character in juxtaposition to Katherine’s human calculations. With its blinking lights and whirling tapes, the huge machine—which occupies a whole room—represents a new phase of computation. Nevertheless, the movie makes clear that even the most sophisticated computer needs human creativity to design it and validate its outcomes; so, physics and mathematics are human endeavours rather than only mechanical ones.

Wind Tunnels and Breakthrough Barriers: Mary Jackson’s Engineering Vision

Although Katherine Johnson’s mathematical computations occupy front stage in most of “Hidden Figures,” the film also offers a striking visual depiction of engineering physics via Mary Jackson’s story (Janelle Mona). Among the most visually stunning depictions of physics ideas in the movie are the sequences including NASA’s wind tunnels.

The wind tunnel’s sequence deftly explains many basic concepts in aeronautical engineering:

First we locate the physical testing environment, a sizable construction designed to imitate the extreme conditions of space flight. The film shows the raw power of supersonic wind forces by means of both visual signals—the shaking of the model spacecraft—and sound design—the loud scream of the tunnel. This offers the physics at work visceral awareness.

The way Mary approaches problem-solving is evident when the model spacecraft breaks down during testing. Rather than abstract computations, we find her pointing out the specific weak points in the heat shield construction, therefore applying thermodynamics and materials physics in a practical way. The movie deftly shows the physics idea of structural integrity under harsh conditions using close-ups of the damaged model.

These sequences are so strong as they link engineering physics to human will. Mary’s quest of an engineering degree obliged her to ask the court to let her enrol in courses at an all-White university. The movie makes a connection between shattering the sound barrier and overcoming societal boundaries: both call for knowledge of current structures and the bravery to go beyond them.

The mathemical concentration of Katherine’s scenes contrasts greatly with this depiction of engineering physics. Mary’s engineering is illustrated through physical testing, materials, and the actual hardware of spaceflight while Katherine’s work is shown through mathematics and trajectories. Collectively, they show how physics exists on a spectrum from theoretical computation to useful application.

From Human Computers to IBM: Dorothy Vaughan’s Digital Foresight

Possibly the most forward-looking portrayal of scientific concepts in “Hidden Figures” is that of Dorothy Vaughan (Octavia Spencer). Through her narrative, the film marks a turning point in scientific history: the move from human calculation to electronic computer.

The film creates a striking visual contrast between the human computers – halls full of women hand-calculating and the huge IBM mainframe NASA has acquired. Presented almost as an alien, the big machine features punch cards, flickering light, and mysterious purposes. Through Dorothy’s perspective, we witness a visualisation of not just computing technology, but of technological paradigm shifts in scientific work.

What struck me most was how the film visualises programming concepts. When Dorothy secretly borrows a FORTRAN programming book and teaches herself the language, we close-ups of code alongside her handwritten notes. The movie graphically compares the new programming syntax she’s learning with the mathematical notation she already knows, therefore illustrating how human mathematical thought turns into computer instructions.

The scene where Dorothy at last gets the IBM functioning successfully visualises something typically invisible: the logical architecture of a computer programme. As she inserts her program cards into the machine and waits for the result, the movie builds tension on whether her directions will be precisely understood by it. Creating visual drama around essentially an abstract logical process is rather remarkable.

Dorothy’s foresight on the future of computing also enables the movie to see a fundamental fact about scientific progress: technology alters how we approach physics and mathematics, but human understanding remains vital. The film shows the continuity between human and electronic computation – illustrating that the physics stays the same even as the instruments change – as she insists on moving her whole staff of women computers into the new electronic computing era.

Expanding Our View: The Physics of Inclusion

“Hidden Figures” accomplishes something remarkable beyond its visualisation of orbital mechanics and engineering physics – it expands our understanding of who contributes to scientific advancement.

The film illustrates how physics and mathematics benefit from diverse perspectives through several key sequences:

When Katherine Johnson identifies a flaw in the existing calculation methods for orbital reentry, we see how fresh eyes can find solutions to seemingly impossible problems. The movie sees this breakthrough not only in the equations themselves but also in Katherine’s original method of approaching the problem by using expertise from several fields.

Likewise, Mary Jackson’s engineering observations result in part from her unique viewpoint on the employed materials. The movie gently implies that diversity in scientific teams results in more solid answers and more innovative methods of approaching physics problems.

For a site like Physics in Frames, “Hidden Figures” particularly resonates since it shows who does the work, therefore transcending just special effects or theoretical ideas in the visualisation of physics concepts. The film corrects our visual perception of scientific history by literally placing these women on screen, doing computations and solving engineering issues advancing mankind’s knowledge of space.

The invisible forces guiding our planet were mapped in part by the physics computations these ladies completed. Likewise, by bringing their tales front and centre, the movie guides us in charting the hitherto unseen contributions of women of colour to our scientific progress.

“Hidden Figures” reminds us as we honour International Women’s Day that physics and mathematics have always been human efforts enhanced by many points of view. The movie presents a more whole and accurate image of who has computed our understanding of the stars, not only visualises orbital mechanics and engineering concepts.

Calculating a Better Future

“”Hidden Figures” is among the most important visualisations of physics in movies not because of amazing effects or mind-bending ideas but rather because of its human truth. The movie teaches us that behind every equation, every spaceship design, and every computer program are people whose commitment and genius forward our knowledge.

“Cinematic representation meets historical reality: The actresses portraying NASA’s pioneering mathematicians (top) alongside the real Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson (bottom). This visual connection between the film’s depiction and historical photographs reminds us that these extraordinary mathematical achievements weren’t fiction but the work of real women whose calculations made space exploration possible.”

On this International Women’s Day, I am reminded that our visualisaton of physics in cinema should incorporate not simply the ideas themselves but also the several minds that have created our knowledge of those ideas. Socially and scientifically, Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson computed routes to the heavens that seemed unthinkable.

The next time you gaze up at the night sky, remember the women who computed those ideas with chalk, paper, and determination and consider the mechanics controlling celestial bodies. Their narrative reminds us that everyone owns physics and that those who keep challenging the cosmos will find its secrets revealed.

Other films you have watched that highlight women’s achievements to engineering, mathematics, or physics? Comments or editor@physicsinframes.com to share your ideas.

Leave a comment